Research - (2022) Volume 12, Issue 9

The medicinal plants of the region of El Oued (south-eastern Algeria) : Inventory and traditional therapeutic uses

N. Hacini1, R. Djelloul1*, L. Boutabia2 and B. Magdoud3Abstract

This work is based on an ethnobotanical inventory of plants used in traditional medicine in the El Oued region. The goal of this work was to enhance the medicinal plants in the region of El Oued through a survey directed to people who have information on medicinal plants and their use in the region as herbalists, traditional healers, nomads, and some of the city population. Therefore, we inventoried 73 plants belonging to 37 families, and the largest are the families Asteraceae and Lamiaceae, with 9 species each.

According to the indigenous population, the spontaneous, local and perennial plants are the most used in the treatment because of their availability in a sustainable environment. Based on these plants and by oral administration with the decoction method of preparation, the population of El Oued uses the natural remedy to treat the majority of digestive and Broncho-pulmonary diseases, representing respectively the rates of (27.22%) and (13.29%).

Keywords

Inventory, Ethnobotany, Medicinal plants, Digestive, Decoction, Broncho-pulmonary.

Introduction

The Sahara is the largest desert but also the most extreme, i.e., the one in which the desert conditions reach their greatest harshness (Ozenda, 1991). The state of the spontaneous flora in this area as well as the relationships between humans and plant species deserve particular attention (Ouled El Hadj et al., 2003).

The spontaneous plant resources of the Sahara constitute a flora of about 500 species of higher plants, some of which are still used today by the populations as medicinal plants (Ozenda, 1983).

Medicinal plants are a numerically large group of economically important plants. They contain active components used in the treatment of various diseases (Bellakhdar, 1997). They remain a source of medical care in developing countries, due to the absence of a modern medical system (Mehdioui and Kahouadji, 2007). According to (Beloued, 2003), traditional medicine has always occupied an important place in the traditions of medicine in Algeria. Over the past few years, the results conducted by specialists (doctors, agronomists, ecologists, economists, etc.) have helped to demonstrate to humans the effects of drugs based on chemical products, the importance, and the effectiveness of medicinal plants and products from organic farming (Messaoudi, 2005).

A better knowledge of plants active against human diseases can lead to the selection, among the many so-called medicinal species used by populations, of a group of plants that are active and non-toxic and can be used by these populations (Lamnaouer, 2002, Amri et al., 2017).

Ethnobotany is a scientific discipline belonging to the field of ethnology that aims to study the traditional use of the plant, its method of preparation, and the diseases it can treat (Boukef, 1986). For this purpose, and according to the interesting results obtained by various authors (Boutabia et al., 2020, Yapi, 2015, Miara et al., 2019), we have suggested this study, which was carried out in southern Algeria. Our contribution falls within the framework of the census of spontaneous medicinal plants to provide additional information on the Algerian wild medicinal flora and its use by the local population to enrich scientific knowledge, to enhance and preserve this heritage of its use reasonably within a framework of sustainable management of these natural resources.

Methodology

Presentation of the study region

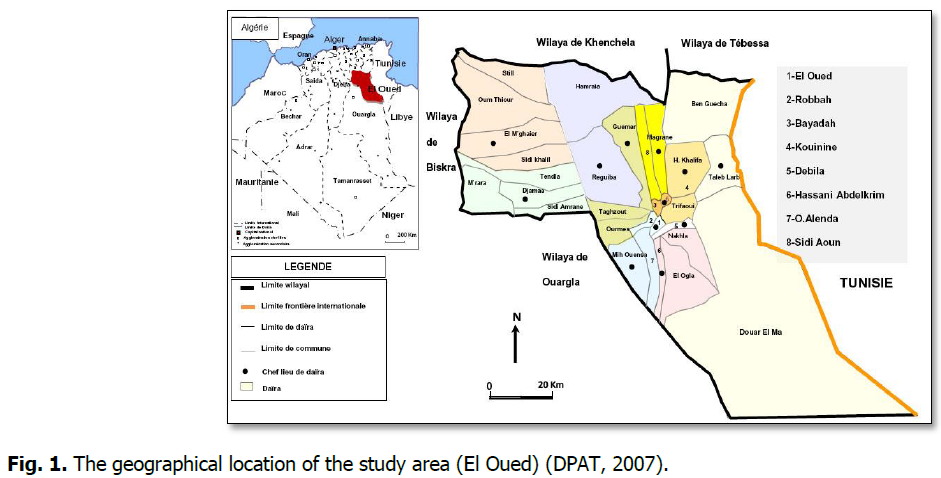

The state of El Oued, which occupies an area of 44,586.80 km2 is limited by the state of Tébessa in the North-East, the state of Khenchela in the North, the state of Biskra in the North-West, by the state of Djelfa in the West, the state of Ouargla in the West and the South, and by the Tunisian border in the East (Fig. 1) (DPAT, 2007).

Fig 1: The geographical location of the study area (El Oued) (DPAT, 2007).

The survey methodology

Our work is based on the study of the use of spontaneous plants in the traditional pharmacopeia of an indigenous population of the region of El Oued. The ethnobotanical survey was carried out using a questionnaire. First, we made an inventory of the plants used for therapeutic purposes. For this step, a simple collection method was adopted, which joins the sheet proposed by (Boukef, 1986).

In a second step, after a prior synthesis of the preliminary data, interviews with our informants provided us with details and various clarifications on the species listed: parts used, method of preparation, therapeutic indications, and routes of administration. For this purpose, we used for our study a questionnaire that was previously translated from French into Arabic and adapted to the objectives of our study, namely: the profile of the informant (age, gender, family situation, level of study); the medicinal plant (local name, scientific name); the part used; the method of preparation; and diseases to be treated (Kadri et al., 2018).

Formalized ethnobotanical survey

The present study concerned the different categories of the population likely to know about plants and their therapeutic uses, such as herbalists, traditional healers, nomads, and city dwellers. For the success of this work, a survey was conducted among people who know medicinal plants, where we questioned a total of 100 people, including 20 herbalists, 40 nomads, and 40 old women. The questionnaire adopted includes the following key questions: (i) Do you know which plants are used in traditional therapy? (ii) What is the local name of these plants? (iii) What parts of this plant are used? (iv) How are they prepared? (v) And what is the form of use?

Analysis of processed parameters

After data collection, Microsoft EXCEL Version 2007 software is used for the graphical representation of calculated results. Most of the plant species that grow all over the world have therapeutic virtues because they contain active principles that act directly on the body (Iserin, 2001). In this part, different parameters have been studied. First, we were interested in the parts used (leaves, stems, roots, flowers, fruits, buds, and seeds), which can have very different functions (food, medicinal, toxic) (Beloued, 2003). The predominance of the use of one organ over another in the therapeutic field derives from the concentration of active ingredients in this organ (Ouled El Hadj et al., 2003, El Hilah et al., 2015, Miara et al., 2019). It is therefore always necessary to specify the organ which is the origin of the drug, the method of preparation of the remedy, and the route of administration. The determination of the mode of preparation of a remedy based on the different plant parts has very high importance, to define the ideal mode which makes it possible to preserve the active substances and give an effective extract and at the same time avoid the extraction of toxic substances (a risk of concentration of heavy metals in plants) (Chevalier, 2001). Moreover, the definition of the modes of administration for each type of preparation and the diseases treated is the main objective of phytotherapy.

Results and Discussion

Through the study that we conducted in the region of El Oued on the uses of plants in traditional medicine, it appears that there is a diversity of practice as regards the symptoms treated, the parts used, and the method of preparation and use. The survey carried out revealed a very diverse list of spontaneous medicinal plants. A summary of the data collected is illustrated in Table 1.

| S.No | Families | Species | Vernacular names | Cultivated/ Spontaneous | Therapeutic uses | Used parts | Preparation mode | Utilization mode |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Apiaceae | Ammodaucus leucotrichus Coss. and Durieu | Oum Driga | Spontaneous | -Kidney stones -Intestinal gases |

Flowers | Decoction | Ingestion |

| 2 | Ferula vesceritensis Coss. and Dur. ex Batt. | Heltita | Spontaneous | -headache | Sure |

|

Inhalation | |

| 3 | Foeniculum vulgare Mill. | Bassbasse | Cultivated | Diuretic Stomach cramp intestinal gas |

Fruits+ Roots |

|

Ingestion Drink |

|

| 4 | Arecaceae | Phoenix dactylifera L. | Palmier dattier | Cultivated | -Infertility -Sexual weakness |

Flowers (pollen) | Powder (mix with honey) | Ingestion |

| 5 | Asteraceae | Artemisia absinthium L. | Chejrat Meriem | Cultivated | -Gallstones -Rougette -Anthelmintic -Antibiotic |

|

Infusion | Ingestion |

| 6 | Artemisia campestris L. | Tougouft | Spontaneous | Fever -Injuries -Toxicity |

Aerial part | Infusion | Ingestion | |

| 7 | Artemisia herba alba Asso | Chih | Spontaneous | - Cough -Intestinal gas -Stomach cramp - Tooth decay - Anxiety |

Leaves Flowers | Decoction | Ingestion | |

| 8 | Ifloga spicata (Forssk.) Sch. Bip. | Oum rouisse | Spontaneous | Intestinal gas | Flowers | Decoction | Ingestion | |

| 9 | Launaea glomerata Hook. f. | Kerechet Larneb | Spontaneous | Cancer | Fruits | Decoction | Pomade | |

| 10 | Launaea resedifolia (L.) Kuntze | Âdhid | Spontaneous | Prostate inflammation | Aerial part | Decoction | Ingestion | |

| 11 | Otoglyphis pubescens (Desf.) Pomel | Gritfa (Ouazouaza) | Spontaneous | Icterus |

|

Decoction | Ingestion | |

| 12 | Rhanterium suaveolens Desf. | Ârfaj | Spontaneous | Skin allergy | Totale | Decoction | Ingestion | |

| 13 | Sonchus asper (L.) Hill | Sag Ghrabe | Spontaneous | -Intestinal inflammation -Antiseptic -skin-sensitivity |

|

Decoction |

|

|

| 14 | Boraginaceae | Arnebia decumbens (Vent.) Coss. and Kralik | Hommiri | Spontaneous | Makeup | Roots | Direct | Pomade |

| 15 | Brassicaceae | Malcolmia aegyptiaca Spreng. | El-Harra | Spontaneous | immune tonic | Aerial part | Decoction | Ingestion |

| 16 | Diplotaxis pitardiana Maire |

Jarjir | Spontaneous | Hear loss |

|

Decoction | Pomade | |

| 17 | Cactaceae | Opuntia maxima Mill. | Hendi | Cultivated | Diarrhea | Leaves | Powder | Ingestion |

| 18 | Caryophyllaceae | Paronychia arabica (L.) DC. | Kssaret Elhajar (Elâyacha) | Spontaneous | -Kidney stones | Underground part | Infusion | Ingestion |

| 19 | Spergularia pycnorrhiza Foucaud ex Batt. |

Bssat Lemlouk | Spontaneous | -Kidney stones -Diuretic |

Total | Infusion | Ingestion | |

| 20 | Chenopodiaceae | Atriplex halimus L. | Ghettaf | Spontaneous +cultivé |

-Kidney stones | Leaves | Decoction | Ingestion |

| 21 | Haloxylon articulatum (Moq.) Bunge |

Remth (Bagel) | Spontaneous | Urinary tract infections | Leaves | Decoction | Ingestion | |

| 22 | Traganum nudatum Delile |

Dhamrane | Spontaneous | Abdominal muscle crisis | Leaves | Powder | Ingestion | |

| 23 | Cucurbitaceae | Colocynthis vulgaris (L.) Schrad. | Hdaj (Hendhal) | Spontaneous | -Sting - Diabetes |

Fruits | Powder | Ingestion |

| 24 | Cucumis pustulatus Naudin ex Hook. f. |

Fagousse l’hamir | Spontaneous | Icterus | Underground part | Decoction | Ingestion | |

| 25 | Cyperaceae | Cyperus conglomeratus Rottb. |

Sâad | Spontaneous | -Asthma - Cough |

Roots | Decoction | Ingestion |

| 26 | Euphorbiaceae | Euphorbia guyoniana Boiss. and Reut. |

Lobbine | Spontaneous | -Diabetes | Flowers | Decoction | Ingestion |

| 27 | Fabaceae | Astragalus gombo subsp. gomboeformis (Pomel) Eug. Ott | Foul lebel | Spontaneous | Complete body food |

|

Powder | Ingestion |

| 28 | Astragalus gyzensis Bunge | D’lilieâa (Hlioua) | Spontaneous | Joint inflammation | Stems | Powder | Pomade | |

| 29 | Ceratonia siliqua L. | kheroube | Cultivated | -Diarrhea -Digestible laxative - Flu |

Grains | Powder | Ingestion Drink |

|

| 30 | Retama raetam (Forssk.) Webb | Retam | Spontaneous | -Cold | Underground part | Infusion | Ingestion | |

| 31 | Trigonella foenum-graecum L. | Helba | Cultivated |

|

Grains | Seffa | Ingestion | |

| 32 | Gentianacees | Centaurium umbellatum | Mararet lehnech | Spontaneous |

|

Aerial part | Decoction | Ingestion |

| 33 | Lamiaceae | Ajuga iva L. | Chendegoura | Spontaneous |

|

Aerial part | Decoction | Ingestion |

| 34 | Lavandula officinalis L. | Khezama | Cultivated | -Cough -Anxiety -Acne -Icterus -Painful periods -Gravel |

|

|

|

|

| 35 | Marrubium vulagare L. | Mriouat | Spontaneous | -Stomach disease -Anthelmintic -toxicity -Cardiotonic |

|

Decoction | Ingestion | |

| 36 | Mentha pulegium L. | Flioue | Spontaneous | -Vomiting - Cough |

Aerial part |

|

Ingestion | |

| 37 | Mentha spicata L. | Nânâa | Cultivated | -Intestinal gas -Intestinal cramp |

Aerial part |

|

Drink Ingestion |

|

| 38 | Ocimum bassillicum L. | Hebak (Naânaâ bouchoucha) | Cultivated | -Regulation of pregnancy -Urinary pain -Intestinal gas |

|

Decoction |

|

|

| 39 | Origanum compactum L. | Zâatar | Spontaneous | -Intestinal gas - Flu -Asthma - Cough -Respiratory antiseptics |

Flowers | Decoction | Ingestion | |

| 40 | Origanum majorana L. | Mardegouche | Cultivated | -Intestinal gas -Tranquilizer -stomach ulcer |

|

Infusion | Ingestion | |

| 41 | Rosmarinus officinalis L. | Klil | Spontaneous | -Intestinal cramps -Intestinal gas -Emmenagogue |

Aerial part | Powder | Ingestion | |

| 42 | Laureaceae | Laurus nobilis L. | Rand | Cultivated | - Cough -Digestible laxative |

|

|

Ingestion |

| 43 | Liliaceae | Androcymbium punctatum (Schlecht.) Cav. | El Haya wa El mayta |

Spontaneous | Lethal herb | Fruits | - | |

| 44 | Asphodelus tenuifolius Cav. | Tazia | Spontaneous | -Cough - Common cold -Diarrhea |

Aerial part |

|

|

|

| 45 | Urginea noctiflora Batt. and Trab. | B’ssile | Spontaneous | Bronchial diseases | Underground part | Infusion | Ingestion | |

| 46 | Lythraceae | Lawsonia inermis L. | Hena | Cultivated | -Stomach cramp -Intestinal gas |

Leaves |

|

|

| 47 | Moringaceae | Moringa oleifera Lam. | Bane/Moringa | Cultivated | -Malnutrition - Cancer - Diabetes -Icterus -urinary disorders -stomach ulcer |

Whole plant |

|

|

| 48 | Myrtaceae | Myrtus communis L. | Rihane | Spontaneous | -Smell from the mouth -Jaundice - Anxiety - Common cold -Injuries -Anorexia |

|

|

Ingestion |

| 49 | Punica granatum L. | Romane | Cultivated | -hemorrhoids - Diabetes -gastric ulcers |

Fruits | Powder | Ingestion | |

| 50 | Syzygium aromaticum (L.) Merr. and L.M.Perry |

Kronful | Cultivated | - Fever -Stomach cramp -Sexual weakness - Anxiety -Anorexia |

Flower petals |

|

|

|

| 51 | Oleaceae | Olea europea L. | Zitoune | Cultivated | - Arterial pressure -Digestible laxative - Fever -Cardiotonic |

|

Decoction |

|

| 52 | Orobanchaceae | Cistanche violacea (Desf.) Hoffmanns and Link |

Thanoun | Spontaneous | Regulation of the menstrual cycle |

|

Decoction | Ingestion |

| 53 | Papaveraceae | Papaver rhoeas L. | Ben Noâmane | Spontaneous | -Cough -Measles -Digestible laxative |

Flowers | Decoction | Ingestion |

| 54 | Pinaceae | Pinus halepensis Mill. | S'nober | Cultivated | -Diuretic | Cortex Bud |

|

Ingestion |

| 55 | Plantaginaceae | Globularia alypum L. | Taselgha | Spontaneous | -Antifungal -Stomach cramp |

Leaves Flowers |

Decoction | Ingestion |

| 56 | Plumbiginaceae | Limoniastrum guyonianum Boiss. | Zaita | Spontaneous | -Stomach ulceration -Intestinal gas -Asthma - Cough |

Leaves Flowers |

|

Ingestion |

| 57 | Poaceae | Cynodon dactylon (L.) Pers. | Najm | Spontaneous | Toxic plant | Flowers | Decoction | Ingestion |

| 58 | Cymbopogon schoenanthus (L.) Spreng. | El Lemmad | Spontaneous | Diuretic -Give appetite -Intestinal disorders -Food poisoning |

Seeds | -Infusion -Decoction | Ingestion | |

| 59 | Schismus barbatus (Loefl. ex L.) Thell. subsp. barbatus | Khafour | Spontaneous | -Flu | Flowers | Decoction | Pomade | |

| 60 | Stipagrostis pungens (Desf.) De Winter | Drinn | Spontaneous | Kidney stones | Aerial part | Decoction | Ingestion | |

| 61 | Zea mays L. | Maïs | Cultivated |

|

Fruits | Powder | Ingestion | |

| 62 | Polygonaceae | Calligonum comosum L’Hérit | L’arta | Spontaneous | Piqure de scorpion | Leaves | Infusion | Drink |

| 63 | Portulacaceae | Portulaca oleracea L. | Pourtlak (Pakla hamka) |

Cultivated | -Regulation of pregnancy -Sexual weaknesses |

Seeds | Infusion | Ingestion |

| 64 | Ranunculaceae | Nigella damascena L. | Haba Saouda | Cultivated | -Anorexia -Cardiotonic |

Seeds | Powder (mix with honey) | Ingestion |

| 65 | Rhumnaceae | Ziziphus lotus L. | Sedra | Cultivated | -Stomach cramp -Injuries |

Leaves Fruits |

|

|

| 66 | Rosaceae | Neurada procumbens L. | Sâadane (Koffice) | Spontaneous | Abdominal muscle crisis | Leaves | Powder | Ingestion |

| 67 | Prunus avium (L.) L. | Hab lemlouk | Cultivated | Digestible laxative | Stems | Direct | Ingestion | |

| 68 | Solanaceae | Solanum nigrum L. | Enb Thibe | Spontaneous | Urine pain | Fruits | Decoction | Ingestion |

| 69 | Tamaricaceae | Tamarix boveana Bunge |

Tarfa | Spontaneous+Cultivated | Icterus |

|

Decoction | Ingestion |

| 70 | Thymeleaceae | Thymelaea microphylla Coss. and Durieu |

Methnane | Spontaneous | -Menstrual congestion -Cardiovascular diseases |

Flowers | Decoction | Ingestion |

| 71 | Zinziberaceae | Zingiber officinale Roscoe | Zanjabil | Cultivated | - Weakness -Stomach cramp - Cough - Diabetes -Intestinal gas - Fever -Anemia |

Aerial part |

|

|

| 72 | Zygophllaceae | Peganum Harmala L. | Harmel | Spontaneous | -Tranquilizer -Rheumatism -Anthelmintic |

Seeds | Powder | Ingestion |

| 73 | Zygophyllum album L. f. | Bougriba (Agga) | Spontaneous |

|

Leaves | Decoction | Drink (Ingestion) | |

Table 1. Categories, therapeutic uses, parts used, methods of preparation, and methods of use.

List of medicinal plants

The population of El Oued is well known for its use of medicinal and aromatic plants. A great part of this population remains attached to its customs and prefers to go to the doctor only after having gone through a traditional treatment (Traditional healers, Achebs, healers, etc.).

Through our survey, it appears that the number of plants used in traditional medicine is 73, 48 of which are spontaneous. The large proportion of spontaneous plants is justified by the fact that a good part of the population surveyed, in the study region, still practices a semi-nomadic way of life.

In general, the northern Sahara includes a significant number of medicinal plants. In their study, (Chehma and Djebar, 2008) were able to count 68 species. In the Ouargla region (Oueld El Hadj et al., 2003), 37 species with therapeutic interests, including 20 spontaneous, were identified, and in El Golea (Azzouz, 2007), 58 species were inventoried, including 51 spontaneous.

The importance of the number of medicinal species in the region of El Oued can be explained by (i) the particularity of the said region by its particular reliefs (Erg) allowing the installation of certain demanding species versus edapho-climatic conditions; (ii). A non-negligible part of the cultivated plants has an origin outside our country, coming in particular from Eastern countries thanks to commercial activities relating to condiments, medicinal and aromatic plants (iii) The survey carried out targeted not only the indigenous population of El Oued but also nomads and herbalists.

Different categories of medicinal plant users in the El Oued region

Spontaneous/cultivated

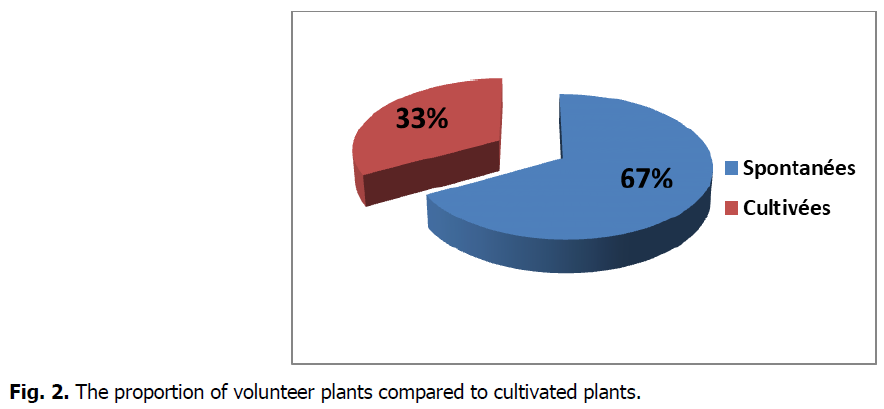

Spontaneous plants are the most used in the traditional pharmacopeia with 67%, or two-thirds of the total species, while the cultivated plants used represent one-third of the total species with 33%. These proportions are due to the high numbers of surveys carried out among the nomads (men of the desert), who use spontaneous plants around their habitats for the treatment of various diseases since there is no cultivation of plants in these completely arid environments (Fig. 2).

Fig 2: The proportion of volunteer plants compared to cultivated plants.

It should be noted that the people questioned believe more in the power of spontaneous plants in curing diseases than in cultivated plants. Indeed, it is known that spontaneous plants have a better concentration of active principles than cultivated plants (Bézanger Beauquesn et al., 1975).

Imported and local

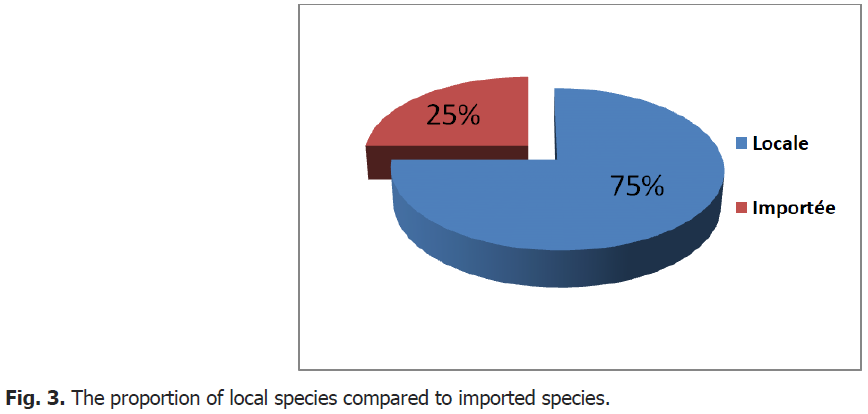

According to Fig. 3, we note that 75% of the plants used in the traditional pharmacopeia of the region of El Oued are local, i.e., species originating from the said region. While 25% of the species mentioned in our survey are imported and therefore come from outside the country.

This could be explained by the fact that the population questioned uses spontaneous plants according to ancient know-how which is based on the exploitation of the natural resources of the region. This result agrees with a previous study (Azzouz, 2007), which was able to find that the species used in the region of El Goléa are local with a rate of (78%). Moreover, the use of imported plants comes from the indications of healers and herbalists.

Fig 3: The proportion of local species compared to imported species.

Specific nature of the families of medicinal plants retained per family

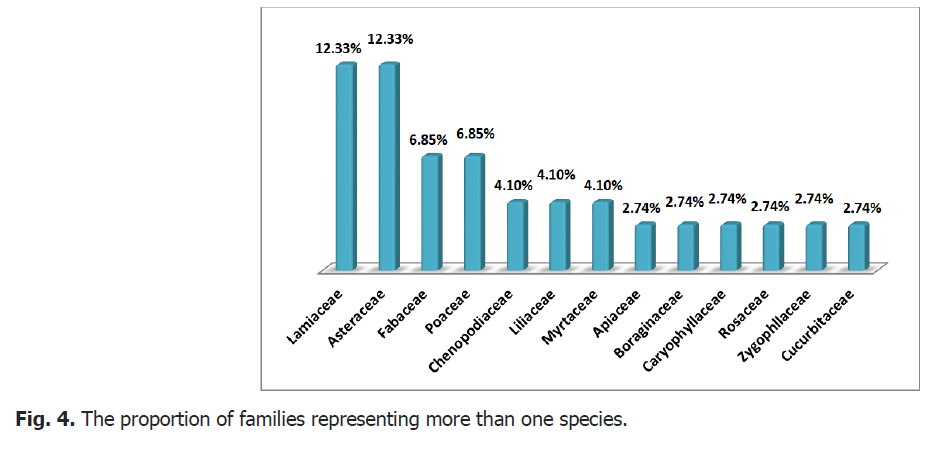

The medicinal species identified belong to 37 families, of which the most important in the number of species, are the Asteraceae and the Lamiaceae, with 9 species (12.33%) of the total species each.

Additionally, more than 64% of the families (24/37) are represented by only one species (Fig. 4). This can be explained by the dominance of these two botanical families in the northern Sahara, in general (Chehma and Djebar, 2005, Chehma, 2006) and in the region of El Oued in particular.

Fig 4: The proportion of families representing more than one species.

This dominance of Asteraceae as a family of medicinal species has been reported by several authors. Indeed, Ould El Hadj and his collaborators (2003) recorded in the Ouargla region the highest proportion of Asteraceae with 13.5%, followed by Poaceae with 10.8%, and Amaranthaceae, Apiaceae, and Labiatea with 8.1% each. For the regions of Ouargla and Ghardaïa, (Chehma and Djebar, 2005) noted that the Asteraceae family represents a rate of 16%, the Amaranthaceae with 11%, followed by the Fabaceae and Poaceae with 6% each.

The different parts of medicinal plants used in the region

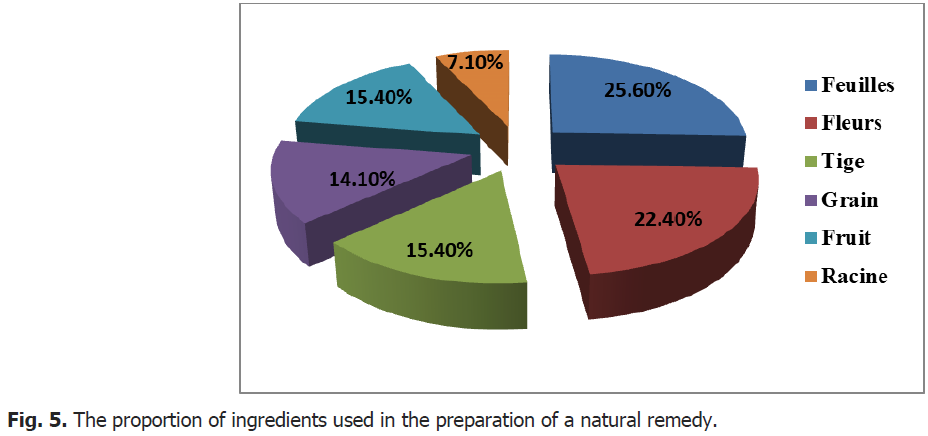

In general, the leaves and the flowers are the parts of the plant the most used in the preparation of the treatments, with respectively 25.6% and 22.4%, followed by the stems and the seeds with a rate of 15.4%, and finally the fruits and roots with 15.4% and 14.1%, respectively (Fig. 5).

Fig 5: The proportion of ingredients used in the preparation of a natural remedy.

The difference in the proportions of the plant organs used is justified by the fact that the concentration of the active principles in the different parts of the plants varies according to the species. It should be reminded that the leaves are the site of the majority of phytochemical reactions and the reservoir of the organic matter derived from them (Chamouleau, 1979).

The work of (Mehdioui and Kahouadji, 2007) indicates that the leaves are the most used parts, with a percentage of 30%. (Ouled El Hadj et al., 2003) recorded a rate of 37.3%; (Yapi et al., 2015) noted a rate of 43.18%; (Benderradji et al., 2021) reported a rate of 47.11%; (Boutabia et al., 2020) mentioned a rate of 56%. Moreover, (Chehma and Djebar, 2005) recorded a utilization rate of 84% for the aerial part, including the leaves. Also, (Azzouz, 2007) found that the leaves represent (44%) and the aerial part in general indicates a rate of (21%). According to (Zabeirou, 2001), the stem, although its main role remains the exchange or the transport of sap through the conductive vessels between the roots and the leaves, can store active substances, particularly in the bark.

In the field, users tend to pull out the whole plant instead of only looking at the desired part (mainly the leaves), it is known that there is a clear relationship between the part of the exploited plant used and the effects of this exploitation on its existence (Bellakhdar, 1997).

Preparation method

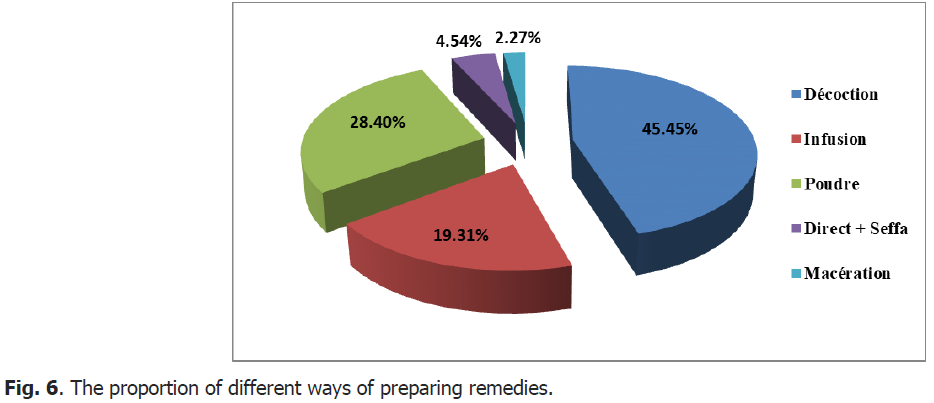

In the region of El Oued, the most commonly used mode of preparation is that of decoction with a rate of 45.45%, followed by powder with 28.4%, infusion with 19.31%, and consumption by the direct mode (or seffa), which means administration without any modification, representing a reduced rate of 4.54%, and finally maceration with 2.27% (Fig. 6).

Fig 6: The proportion of different ways of preparing remedies.

The results relating to the dominance of the use of the decoction mode and the predominance of the powder mode agree with those obtained by (Mehdioui and Kahouadji, 2007) in their study on medicinal plants in Morocco.

On the other hand, previous studies show that the mode of preparation by infusion represents rates of 50% and 20.45% (Chehma and Djebar, 2005, Ouled El Hadj et al., 2003). Moreover, in Algeria, recent studies conducted by (Allali et al., 2008, Hamel et al., 2018, Hamza et al., 2019, Boutabia et al., 2020, Benderradji et al., 2021) indicate that the mode of preparation most commonly used is that of infusion.

Treatment of symptoms

The assessment of spontaneous plants, whose essential objective in phytotherapy is the knowledge of diseases treated by plants, is necessary to determine the different uses and the diseases that differ in humans.

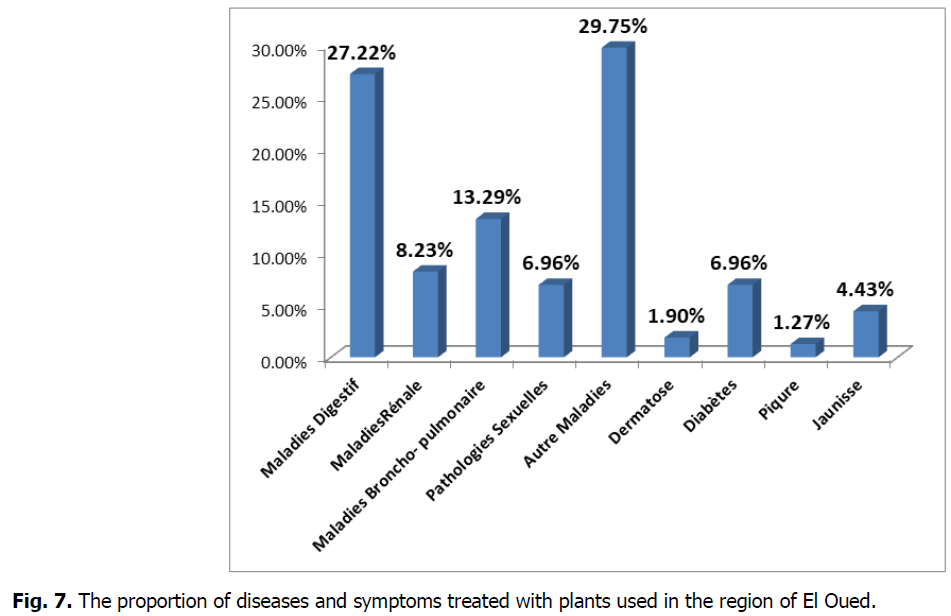

In El Oued region, the majority of diseases treated are presented with a rate of 29.75% for a wide range of diseases covering 27 symptoms and diseases (Fig. 7). To this end, diseases of the digestive system dominate with a rate of 27.22%, followed by broncho-pulmonary diseases with 13.29%, kidney diseases with 8.23%, diabetes, and sexual pathologies with 6.96% each, icterus with 4.43%, and finally dermatosis and insect bites with 1.9% and 1.27%, respectively.

The dominance of digestive system diseases is confirmed by several authors (Mehdioui and Kahouadji, 2007) in Morocco, (Hammiche and Gheyouche, 1988, Ouled El Hadj et al., 2003, Chehma and Djebar 2005, Benderradji et al., 2021) in Algeria.

Fig 7: The proportion of diseases and symptoms treated with plants used in the region of El Oued.

Forms of use

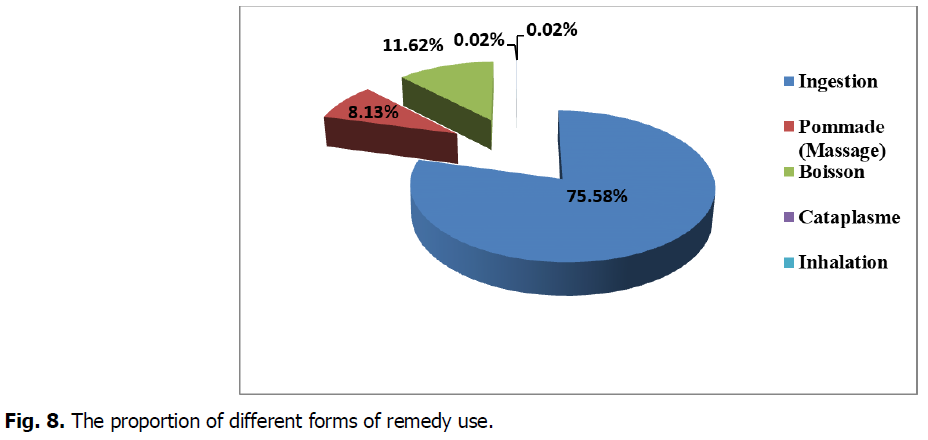

For the application of treatments for the various symptoms mentioned above, we encountered different forms of use, of which the most used in the study area is ingestion with a proportion of 75.58%, followed by drinking with 11.62%, by the ointment (massage) with 8.13% and finally by the cataplasm and the inhalation with very reduced rates, i.e., 0.02% each (Fig. 8). These results are consistent with those of Chehma and Djebar (2008).

Fig 8: The proportion of different forms of remedy use.

The dominance of oral administration in the present study is confirmed by the work of (Ould El Hadj et al., 2003, Messaoudi, 2005) indicating that this mode of administration includes the majority of preparation methods: infusion, maceration, and decoction.

According to other investigations, oral administration remains the most frequently used form of use because it is the most recommended and user-friendly. In addition, it goes hand in hand with the dominance of the decoction, powder, and infusion preparation methods that we have recorded (Azzouz, 2007, Yapi et al., 2015, Kadri et al., 2018).

Conclusion

The ethnobotanical study was carried out in the regi on of El Oued (Sahara-East Algeria), which allowed us to make an evaluation of the medicinal plants' diversity in the said region on the one hand, and to have an idea regarding the use of these plants in the traditional treatment of various affections on the other hand. According to the survey conducted, we noted that the use of spontaneous medicinal plants is dominant compared to cultivated plants. Interestingly, we recorded 73 plants with therapeutic interests, i.e., 48 spontaneous and 25 cultivated. The species used belong to 37 families, the most important of which are those of Asteraceae and Lamiaceae, with a rate of (12.33%). The remaining 64% of families are characterized by only one species. The concentration of the active substances in the different parts of the plant defines their uses. As a result, the leaves are the most used part, followed by the flowers, seeds, stems, fruits, and roots. The decoction is the most frequently used mode of preparation with a rate of (45.45%), followed by powder (28.4%), infusion (19.31%), direct consumption (or seffa) (4.54%), and finally maceration (2.27%). In addition, we emphasized a diversity of symptoms treated by medicinal plants in the study area, the most common of which would be digestive diseases, followed by broncho-pulmonary diseases, kidney diseases, diabetes, sexual pathologies, icterus, and bites. The forms of use are multiple, the most popular of which is ingestion, followed by drinking, ointment, and finally cataplasm and inhalation.

To better understand, preserve, valorize and use spontaneous plant resources with maximum efficiency in the therapeutic field, we wish to continue our study by addressing other aspects relating to phytochemistry, cosmetology, and phytopharmacy in the region of El Oued and elsewhere in Algeria.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Algerian Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research; Directorate General for Scientific Research and Technological Development, “Functional and Evolutionary Ecology”research laboratory, Faculty of Natural and Life Sciences, Chadli Bendjedid University, El Tarf, Algeria.

Conflict of Interest

The authors of this manuscript declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

Allali, H., Benmehdi, H., Dib, M.A., Tabti, B., Ghalem, S., Benabadji, N. (2008). Phytotherapy of diabetes in west Algeria. Asian Journal of Chemistry, 20:2701.

Amri, B., Martino, E., Vitulo, F., Corana, F., Ben-Kaâb, L.B., Rui, M., Collina, S. (2017). Marrubium vulgare L. leave extract: Phytochemical composition, antioxidant and wound healing properties. Molecules, 22:1851.

Azzouz, M. (2007). Etude ethnobotanique de la flore spontanée médicinale dans la région d’El Goléa (El Meniaa). Mém Ing Université d’Ouargla, Algérie, p:57.

Benderradji, L., Bounar, R., Ghadbane, M. et Rebbas, K. (2021). Etude ethnobotanique comparative et utilisation thérapeutique de plantes médicinales de djebel djedoug (Hammam Dhalaa) et du milieu oasien (oasis de Boussaâda). Journal of Oasis Agriculture and Sustainable Development, 3:1-12.

Bellakhdar, J. (1997). Pharmacopée marocaine traditionnelle. Ibis press.

Beloued, A. (2003). Plantes médicinales d'Algérie. Office des Publications Universitaires, Alger, p:284.

Bézanger-Beauquesne, L., Pinkas, M., Torck, M. (1975). Les plantes dans la thérapeutique moderne. Maloine.

Boukef, M.K. (1986). Les plantes dans la médecine traditionnelle tunisienne. Agence de Coopération Culturelle et Technique.

Boutabia, L., Telailia, S., Cheloufi, R., Chefrour, A. (2010). The medicinal flora of the forest massif of Oum Ali (Zitouna-wilaya of El Tarf-Algeria): inventory and ethnobotanical study. Proceedings of the 15th INRGREF Scientific Days: “Valorization of Non-Timber Forest Products, pp:28-29.

Boutabia, L., Telailia, S., Menaa, M. (2020). Traditional therapeutic uses of Marrubium vulgare L. by local populations in the Haddada region (Souk Ahras, Algeria). Ethnobotany Research and Applications, 19:1-11.

Chamloulou, A. (1979). Les usages externes de la phytothérapie. Ed. da Maloine S.A., Paris, p:27.

Chehma, A. (2006). Catalogue des plantes spontanées du Sahara septentrionale algérien. Ed. Dar El Houda, University de Ouargla, p:140.

Chehma, A., Djebar, M.R. (2008). Les espèces médicinales spontanées du Sahara septentrional algérien: distribution spatio-temporelle et étude ethnobotanique. Synthèse: Revue des Sciences et de la Technologie, 17:36-45.

Chevalier, A. (2001). Encyclopédique des plantes médicinales. Identification, préparation, sains. Edition Larousse, Paris, p:335.

DPAT. (2007). Direction de la planification et de l'aménagement du territoire d'El Oued. Annuaire Statistique de la Willaya d’El Oued, p:119.

El Hilah Fatima, F.B.A., Dahmani, J., Belahbib, N., Zidane, L. (2015). Étude ethnobotanique des plantes médicinales utilisées dans le traitement des infections du système respiratoire dans le plateau central marocain. Journal of Animal and Plant Sciences, 25:3886-3897.

Hamel, T., Sadou, S., Seridi, R., Boukhdir, S., Boulemtafes, A. (2018). Pratique traditionnelle d’utilisation des plantes médicinales dans la population de la péninsule de l’edough (nord-est algérien). Ethnopharmacologia, 59:65-70.

Hammiche, V., Gueyouche, R. (1988). Plantes médicinales et thérapeutiques. 1ère partie. Les plantes médicinales dans la vie moderne et leur situation en Algérie. Annales de l’INA El Harrach, 12:419-433.

Hamza, N., Berke, B., Umar, A., Cheze, C., Gin, H., Moore, N. (2019). A review of Algerian medicinal plants used in the treatment of diabetes. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 238:111841.

Iserin, P. (2000). Encyclopedie des plantes médicinales. Larousse VUEF, 2nd Ed., Paris, 14:275.

Yasser, K., Abdallah, M., Abdelmadjid, B. (2018). Étude ethnobotanique de quelques plantes médicinales dans une région hyper aride du Sud-ouest Algérien «Cas du Touat dans la wilaya d’Adrar». Journal of Animal and Plant Sciences, 36:5844-5857.

Lamnaouer, D. (2002). Plantes médicinales du Maroc : Usages et toxicité. Département de Pharmacie-toxicologie, Institut Agronomique et Vétérinaire Hassan II, Rabat-Instituts, Maroc.

Mehdioui, R., Kahouadji, A. (2007). Ethnobotanical study among the local population of the Amsittène forest: case of the Commune of Imi n'Tlit (Province of Essaouira). Bulletin of the Scientific Institute, Rabat, Life Sciences Section, 29:11-20.

Messaoudi, S. (2005). Les plantes médicinales. Ed. Dar El Fiker, Tunis, p:496.

Miara, M.D., Bendif, H., Rebbas, K., Bounar, R., AitHammou, M., et Maggi, F. (2019). Medicinal plants and their traditional uses in the highlands region of Bordj Bou Arreridj (Northeast Algeria). Journal of Herbal Medicine, 16:1-56.

El Hadj, M.O., Hadj-Mahammed, M., Zabeirou, H., Chehma, A. (2003). Importance des plantes spontanées médicinales dans la pharmacopée traditionnelle de la région de Ouargla (Sahara Septentrional-Est Algérien). Sciences and Technologie C, Biotechnologies, pp:73-78.

Quézel, P., Santa, S. (1962). Nouvelle flore de l'Algérie et des régions désertiques méridionales.

Ozenda, P. (1991). Flore de Sahara, Paris, Éd. du GNRS, p:662.

Zabeirou, H. (2001). Contribution à l’inventaire et à l’étude physico-chimique des plantes spontanées médicinales de la région d’Ouargla. INFS As, Ouargla.

Yapi, A.B., Zirihi, G.N. (2015). Etude ethnobotanique des Asteraceae médicinales vendues sur les marches du district autonome d’Abidjan (Côte d’Ivoire). International Journal of Biological and Chemical Sciences, 9:2633-2647.

Author Info

N. Hacini1, R. Djelloul1*, L. Boutabia2 and B. Magdoud32Agriculture and Ecosystem Functioning Laboratory, Faculty of Nature and Life Sciences, Chadli Bendjedid University, El Tarf, Algeria

3Faculty of Nature and Life Sciences, Chadli Bendjedid University, El Tarf, Algeria

Citation: Hacini, N., Djelloul, R., Boutabia, L., Magdoud, B. (2022). The medicinal plants of the region of El Oued (south-eastern Algeria): inventory and traditional therapeutic uses. Ukrainian Journal of Ecology. 12:1-16.

Received: 15-Sep-2022, Manuscript No. UJE-22-74841; , Pre QC No. P-74841; Editor assigned: 17-Sep-2022, Pre QC No. P-74841; Reviewed: 28-Sep-2022, QC No. Q-74841; Revised: 03-Oct-2022, Manuscript No. R-74841; Published: 07-Oct-2022, DOI: 10.15421/2022_398

Copyright: This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.