Research Article - (2021) Volume 0, Issue 0

Cluster analysis in ethological research

T. V. Antonenko1*, S. V. Pysarev2, A. V. Matsyura1 and E. V. Antonenko1Abstract

Big cats are often on display in zoos around the world. The study of their time budget is the basis of ethological research in captivity. The paper considers the features of the behavior of the subfamily Pantherinae, the daily activity of animals in the summer, methods of keeping, the exposition of enclosures, and relationships with keepers. The studies were conducted in the summer of 2012 and 2013 at the Barnaul Zoo. The total observation time for the animals was 120 hours. The behavior of the African lion (Panthera leo leo – male), the Ussuri tiger (Panthera tigris altaica – female), and the Amur leopard (Panthera pardus orientalis – male) has been studied. In the course of the work, the compilation of ethograms, continuous recording, and free observations were used. The clustering method was applied to analyze the patterns of behavior of animals in captivity. Cluster analysis breaks down the behavior of captivities animals into two large blocks. Locomotion in animals should be considered as a separate block. The animal’s growth and development period require a high proportion of physical activity, which is noticeable when observing the Amur tiger. Locomotion occupied 32.8% of the total time budget of this animal. Large cats have never been in a shelter (in wooden structures of the appropriate size). They used the roof of the houses only as a place for rest and observation. The proportion of marking, hunting, eating, exploratory behavior, grooming, and such forms of behavior as freezing, static position, orienting reaction did not differ significantly. Play behavior with elements of hunting and manipulative activity took 5.5% of the Amur tiger’s time budget for the period under review. We associate this primarily with the age of the given animal. Play behavior was observed two times less often in the Far Eastern leopard (2.9%) and African lion (2.6%).

Keywords

Big cats, captive animals, environmental enrichment, cluster analysis, Pantherinae.

Introduction

Behavioral expressions need a mathematical approach to unravel their organization and meaning (Advanced behavioral screening: automated home cage ethology (Spruijt, De Visser, 2006).

The primary purpose of cluster analysis is to divide objects and features into homogeneous groups or clusters appropriately. This means that classifying the data and identifying the corresponding structure in it is being solved. Cluster analysis allows dividing objects not by one parameter but by a whole set of features (Bureeva, 2007). Besides, unlike most mathematical and statistical methods, cluster analysis does not impose any restrictions on the type of objects under consideration and allows one to consider various initial data, including ethological data.

One of the essential tasks of zoos today is environmental protection. It is conducted in two directions: keeping and breeding rare animals and environmental education of the population. Since zoos play an important role in preserving the planet’s biodiversity, any of them must necessarily contain rare species of animals, for which comfortable conditions and the opportunity for reproduction have been created (Veselova, Blokhin, Gilitskaya, 2013). Representatives of the feline family are often kept in zoos all over the world and always attract visitors’ attention (Papaeva, Neprintseva, 2011). In captivity, felines spend more time inactive during the day than in wild representatives of their species (Margualis, Hoyos, Anderson, 2003; Roesch, 2003). Despite this, they can ideally exist in captivity, produce viable offspring and exhibit a natural behavioral repertoire. However, this requires painstaking work on the part of the zoo staff.

Positive attitudes towards keepers’ animals, good subject knowledge, and familiarity with the species are linked to positive behavioral responses. Staff with negative attitudes towards animals or those who lack a good level of experience or education should be avoided in keepers working with exotic species. This will ensure a positive relationship between the animal and the keeper, which reduces stress and increases animal welfare (Ward, Melfi, 2015). Starting research a new group of animals in captivity, it is necessary to get an idea of their ethological characteristics, daily activity, methods of keeping them, feeding, exposing enclosures, and relationships with staff.

The aim of this article was a comprehensive study of the behavior of large cats in the Barnaul Zoo, their time budget, identification of pathological behavior in representatives of the subfamily Pantherinae, analysis of the conditions of keeping animals.

Materials and Methods

The studies were conducted in the summer of 2012 and 2013 at the Barnaul Zoo. The total observation time for the animals was 120 hours.

The behavior of the African lion (Panthera leo leo – male), the Ussuri tiger (Panthera tigris altaica – female), and the Amur leopard (Panthera pardus orientalis – male) has been studied.

In the course of the work, the compilation of ethograms, continuous recording, and free observations were used. The Shorygin coefficient was calculated [Popov, Ilchenko, 2008]. Photo and video filming were carried out. All animals were kept in enclosures equipped with wooden shelves, logs, and hiding houses. The enclosures had an area that was not visible to visitors, except the Far Eastern leopard. The animals were fed according to the rations adopted at the Barnaul Zoo.

The following behaviors were recorded:

1. Natural physical activity (locomotion, manipulation of the interior of the enclosure, hunting, forage, research, and marking behavior);

2. Pathological forms of behavior (pacing, being in a shelter);

3. Inactive behavior (lack of physical activity).

Results and Discussion

Representatives of the Pantherinae subfamily in the Barnaul Zoo are kept in similar habitats. Their aviaries are equipped with wooden houses, which they use as a refuge and as an option for possible vertical movement. Thanks to the activities of the keepers, early socialization of animals take place in the zoo.

The animals kept in the zoo received a varied diet, including live food (rats, guinea pigs, rabbits).

Time budget has been studied in all big cats. To assess the welfare of the animal’s condition, it is essential to quantitatively estimate the time budgets and analyze the causes of such pathological forms of behavior as motor stereotypes, pathological immobility, prolonged stay in a shelter from the elements. Based on these data, the share of each of the elements in the total observation time is calculated (Table 1).

| Patterns of behavior | The proportion of total observation time, % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Tiger | Lion | Leopard | |

| Sleep (lies with opened eyes) | 18.0 | 23.7 | 23.2 |

| Rest (lies with closed eyes) | 12.8 | 21.6 | 11.8 |

| Watchful rest (lies. moves with ears) | 4.3 | 5.0 | 4.1 |

| Freezing (stands still) | 2.3 | 2.7 | 2.7 |

| Motion into the cage (locomotion) | 32.8 | 9.4 | 15.2 |

| Stereotyped behavior (pacing) | 4.9 | 13.2 | 19.6 |

| Play behavior | 5.5 | 2.9 | 2.6 |

| Feeding behavior | 3.0 | 2.7 | 2.8 |

| Grooming | 2.7 | 3.5 | 3.4 |

| Exploratory behavior | 2.5 | 3.3 | 3.0 |

| Hunting behavior | 2.6 | 3.1 | 3.6 |

| Orientation behavior | 4.1 | 2.9 | 3.1 |

| Static behavior | 2.6 | 3.2 | 2.7 |

| Marking behavior | 1.9 | 2.8 | 2.2 |

Table 1. A time budget of some Pantherinae animals at the Barnaul Zoo.

Most of the time budget of the species under consideration is occupied by sleep and rest (from 35.1% to 50.3%). In nature, with a sufficient abundance of food resources, cats also spend much time in an inactive (sleeping. dozing. lying) or inactive state (auto- or allogrooming).

However, an animal in a zoo faces other problems - the scarcity of the environment. the absence of social partners, the inability to use their cognitive abilities (in nature. animals constantly have to solve such problems), insufficient size of the enclosure. As a reaction to all of the above results in stereotypical behavior - a kind of self-therapy for animals experiencing stress of different etiologies. In the leopard - lion - tiger series. the proportion of stereotypical behavior decreases 19.6% - 13.2% - 4.9%, respectively.

The Amur tiger is the youngest animal of the considered species. A relatively high proportion of the stereotyped African lion can be explained by social deprivation because, in nature, these felines live in the prides. It is necessary to carry out measures to enrich the predators’ environment under consideration to reduce the proportion of stereotypes to the minimum values (it is impossible to eliminate pacing. since no experiments can replace the natural habitat).

The animal’s growth and development period require a high proportion of physical activity, which is noticeable when observing the Amur tiger. Locomotion occupied 32.8% of the total time budget of this animal.

Large cats have never been in a shelter (in wooden structures of the appropriate size). They used the roof of the houses only as a place for rest and observation. The proportion of marking, hunting, eating, exploratory behavior, grooming, and such forms of behavior as freezing, static position, orienting reaction did not differ significantly.

Play behavior with elements of hunting and manipulative activity took 5.5% of the Amur tiger’s time budget for the period under review. We associate this primarily with the age of the given animal. Play behavior was observed two times less often in the Far Eastern leopard (2.9%) and African lion (2.6%).

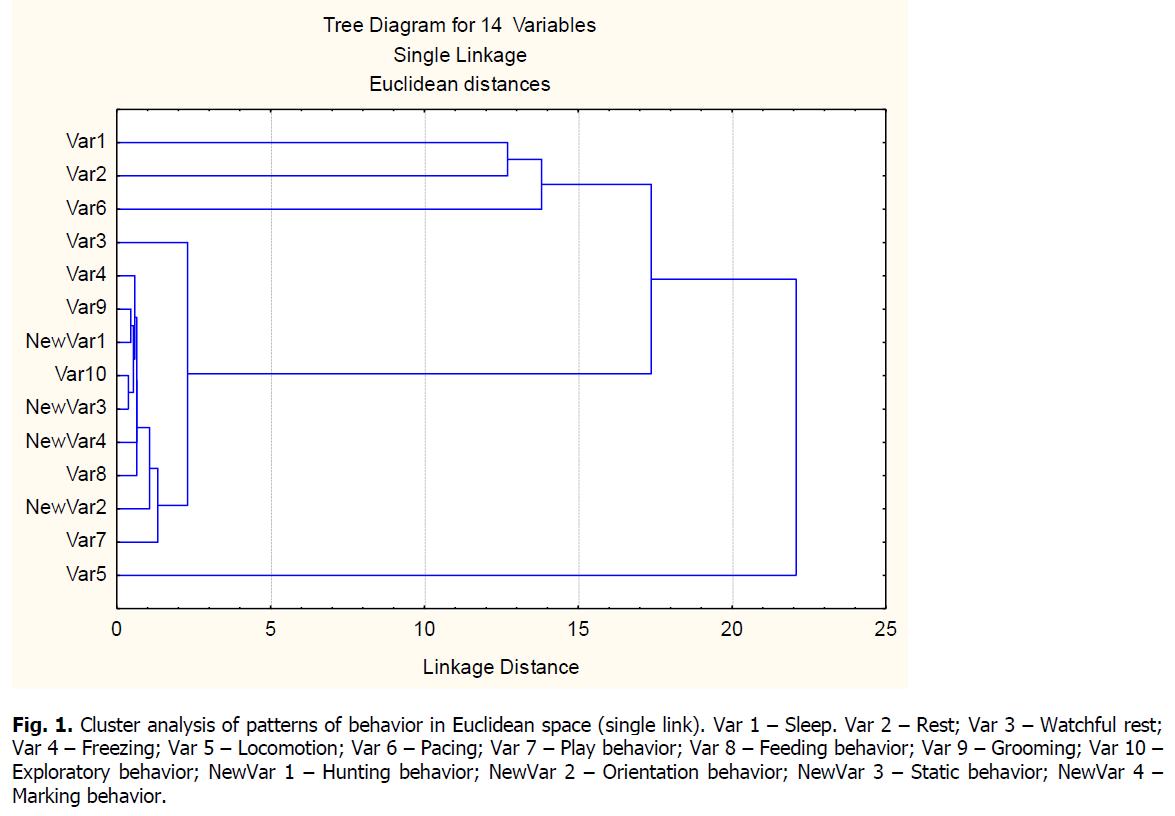

Groups of ethological elements were identified, and a horizontal tree-like diagram was compiled during statistical processing of quantitative relationships of behavioral patterns by the method of cluster analysis. In this chart, the horizontal axes represent the joint distance. So. for each node in the “behavioral pattern” column (its quantitative equivalent) - (where a new cluster is formed), it is possible to see the distances for which the corresponding elements are linked into a new single cluster. When data has a clear “structure” in terms of clusters of objects similar to each other, this structure is likely reflected in the hierarchical tree by different branches.

Individual behavioral elements are combined into two large clusters - inactive behavior (sleep. rest) and stereotypy, natural physical activity. A separate cluster is a movement along with a cell of a non-pathological nature, which is the most distant from others - the distance to the nearest clusters is maximum and equal to 22. The union or the tree clustering method is used to form clusters of dissimilarity or distance between objects. These distances can be defined in one-dimensional or multidimensional space. We have used Euclidean distance as the most common type of distance, geometric distance in multidimensional space.

In a broad sense, distances reflect such a concept as difference, which is dual to the concept of similarity, and the elements of the difference matrix (in general. the matrix of divergences) are dual to the elements of the similarity matrix (in general. the matrix of convergence). By measuring distance, we can talk not only about similarity but also about the difference.

To calculate this distance, we used Single Linkage in Euclidean space. Thus, using a single link (nearest neighbor method), the distance between two clusters is determined by the distance between the two closest objects (nearest neighbors) in different clusters. This rule should, in a sense, string objects together to form clusters, and the resulting clusters tend to be long chains.

Sleep and rest are similar elements (Figure. 1). Stereotypy also fell into the same cluster, which is understandable given the characteristics of its manifestation. It takes up a significant portion of the activity budget of the cats in question. Pacing is of great importance only in the African lion and the Far Eastern leopard.

Figure 1: Cluster analysis of patterns of behavior in Euclidean space (single link). Var 1 – Sleep. Var 2 – Rest; Var 3 – Watchful rest; Var 4 – Freezing; Var 5 – Locomotion; Var 6 – Pacing; Var 7 – Play behavior; Var 8 – Feeding behavior; Var 9 – Grooming; Var 10 – Exploratory behavior; NewVar 1 – Hunting behavior; NewVar 2 – Orientation behavior; NewVar 3 – Static behavior; NewVar 4 – Marking behavior.

The second large cluster is natural physical activity combined with a large number of elements: alert rest, movement with fading, play, food, research, hunting, marking behavior, and grooming, orienting reactions, and static position (when the animal can be located on the interior of the enclosure and actively observe objects of interest). A particular position is the locomotor activity of cats, which occupies a considerable share of all animal activity budgets. However, in the African lion and Far Eastern leopard, it was less (table) than in the Amur tiger. Due to its age, non-pathological activity prevailed in the tiger (32.8%).

Cluster analysis breaks down the behavior of captivities animals into two large blocks. Locomotion in animals should be considered as a separate block.

Conclusions

1. The expositions of large cats’ enclosures in the Barnaul Zoo are practically the same. A friendly attitude of keepers towards cats was noted. We registered the constant change in the animals’ diet.

2. The maximum motor activity of a non-pathological nature was found in the Amur tiger (32.8%). Pathological behavior was observed in the Far Eastern leopard – the pacing (19.4%).

3. Using the cluster analysis method, two large clusters (sleep, rest, and pacing), a cluster of natural behavior, and a particular feline locomotion position were identified.

References

Bashaw M. J., Kelling A. S., Bloomsmith M. A. & Maple T. L. 2007. Environmental effects on the behavior of zoo-housed lions and tigers, with a case study of the effects of a visual barrier on pacing. Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science. 10, 95-109.

Bashaw, M. J. (2003). Consistent effects of controllability of environmental events? In: Bashaw M. J., Kelling A. S., Bloomsmith M. A. & Maple T. L. 2007. Environmental effects on the behavior of zoo-housed lions and tigers, with a case study of the effects of a visual barrier on pacing. Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science. 10, 95-109. Burgener N., Gusset M. & Schmid H. 2008. Frustrated appetitive foraging behavior, stereotypic pacing, and fecal glucocorticoid levels in snow leopards (Uncia uncia) in the Zurich Zoo. Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science. 11, 74-83.

Bureeva. N.N. (2007). Multivariate statistical analysis using PPP “STATISTICA.” and mechanics “. Nizhny Novgorod. 112.

Jenny S. & Schmid H. 2002. Effect of feeding boxes on the behavior of stereotyping Amur tigers (Panthera tigris altaica) in the Zurich Zoo, Zurich, Switzerland. Zoo Biology. 21, 573-584.

Margualis. S.W., Hoyos. C., Anderson. M. (2003). Effect of felid activity on zoo visitor interest. Zoo Biology, 22, 587-599.

Mason G. J. 2010. Species differences in responses to captivity: stress, welfare and the comparative method. Trends in Ecology and Evolution, 25, 713-721.

Mason G., Clubb R., Latham N. & Vickery S. 2007. Why and how should we use environmental enrichment to tackle stereotypic behaviour? Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 102, 163-188.

Mason, G.J., 1991. Stereotypies: a critical review. Animal Behaviour. 41, 1015–1037. Melfi V. 2013. Is training zoo animals enriching? Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 147, 299-305.

Mills D. & Luescher L. 2008. Veterinary and pharmacological approaches to abnormal repetitive behaviour. In: Mason G. & Rushen J. Stereotypic Behaviour in Captive Animals: Fundamentals and Applications for Welfare, 2nd ed. CAB International, Wallingford.

Morgan K. N. & Tromborg C. T. 2007. Sources of stress in captivity. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 102, 262-302.

Roesch. H. (2003). Olfactoty environmental enrichment of felids and the potential uses of conspecific odours. A thesis of degree a master of science in Zoology. Institute of veterinary, animal and biomedical sciences. Massey University, 211.

Papaeva. N.A., Neprintseva. E.S. (2011). The influence of visitors on the behavior of cats at the Moscow Zoo. Communication 1. Use of open-air cage spaces. Scientific research in zoological parks, 27, 77-88.

Popov. S.V., Ilchenko. O.G. (2008). Zoo Research Manual: Guidelines for Ethological Observation of Mammals in Zoos. Moscow: Moscow Zoo.

Spruijt. B.M., De Visser. L. (2006) Advanced behavioural screening: automated home cage ethology. Drug Discovery Today: Technologies, 3(2), 231-237.

Swaisgood R. R. & Shepherdson D. J. 2005. Scientific approaches to enrichment and stereotypies in zoo animals: what’s been done and where should we go next? Zoo Biology. 24, 499-518.

Veselova. N.A., Blokhin. G.I., Gilitskaya. Yu.Yu. (2013). Analysis of the influence of olfactory enrichment of the environment on the behavior of some representatives of the cat family (Felidae) in artificial conditions. Natural and technical sciences, 6(68),127-133.

Ward. S.J., Melfi. V. (2015). Keeper-Animal Interactions: Differences between the Behaviour of Zoo Animals Affect Stockmanship. DOI: doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0140237

Westlund K. 2014. Training is enrichment – and beyond. Applied Animal Behaviour Science. 152, 1-6.

Author Info

T. V. Antonenko1*, S. V. Pysarev2, A. V. Matsyura1 and E. V. Antonenko12Barnaul Zoo, Russia

Citation: Antonenko, T.V., Pysarev, S.V., Matsyura, A.V., Antonenko, E.V. (2021). Cluster analysis in ethological research. Ukrainian Journal of Ecology, 11 (2), Ecological Risk Assessment.

Received: 11-Jan-2021 Accepted: 16-Feb-2021 Published: 02-Mar-2021

Copyright: This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.